“Phase 1 cancer studies, which guide dose selection for subsequent studies, are almost 3 times more prevalent than phase 3 studies and have a median study duration considerably longer than 2 years, which constitutes a major component of drug development time.”

It takes a long, long time for new cancer treatments to get through the necessary clinical trials and reach FDA approval. The median duration for phase 1 oncology trials is around 32 months, and late-stage trials (phases 2 and 3) have seen their times steadily rise in recent years. It stands to reason that if you can safely reduce trial durations, then these life-saving therapies can become available sooner.

But is there a safe and effective way to reduce phase 1 oncology trial durations?

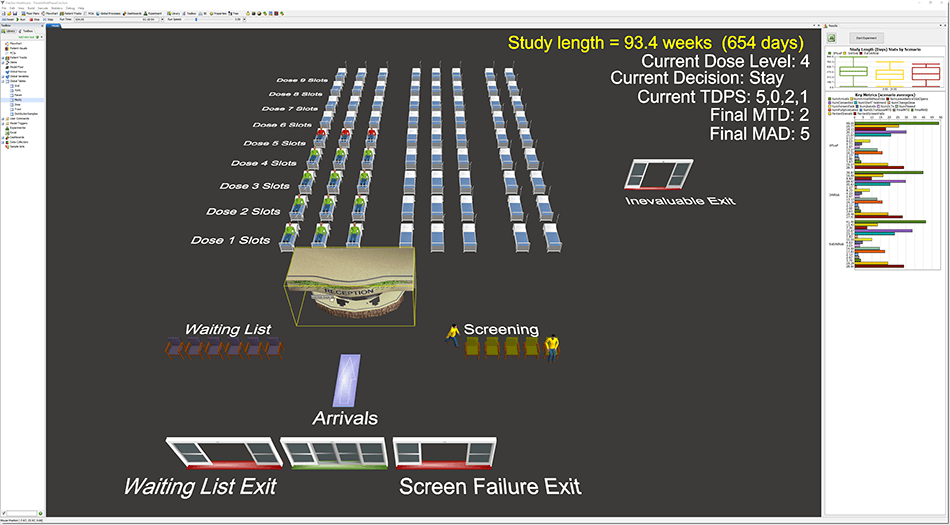

A new study—from researchers at City of Hope, USC’s Norris Cancer Center, and the University of California, Davis—could be an answer to this question. Using FlexSim HC, they were able to validate a new phase 1 trial design that makes simple modifications to the 3+3 and Rolling 6, two commonly used designs.

Change is inevitable

What exactly causes delays in phase 1 oncology trials? There are many specific and well-researched causes, but the reality is that delays happen when things don’t go according to plan. In the world of clinical trials, it’s safe to assume that this will be the norm—you’re going to have screen failures, inevaluable patients, etc. Tried-and-true clinical trial designs like the 3+3 and Rolling 6 aren’t well-suited to respond to these inevitable changes, and the delays will add to the overall trial duration.

This is where the new study comes in. It takes an operations research approach to the problem, focusing on the patient queue and evaluation process. The resulting queue-based designs (IQ 3+3 and IQ Rolling 6) modify the decisions in their parent designs to better accommodate the phase 1 queue.

Here’s an example of one of these modifications from the study:

“For the IQ 3+3 design (Table 1; row 4), enrolling a fourth patient at the same dose level, knowing that 1 of 3 patients has a pass with 2 patients pending, is considered less risky than putting 3 patients at risk without any patient data, as is permitted by the 3+3 design, so this modification does not exceed the risk allowed by the 3+3 but rather starts a patient through the process in case a patient who started earlier is considered not to meet screening criteria or becomes inevaluable. This is the key principle behind the IQ 3+3 design.”

Results and actual use

FlexSim Healthcare was chosen to model and simulate the various designs in a virtual environment. Researcher Paul Frankel said FlexSim Healthcare’s simulation speed was convenient for their study, and it also provided easier debugging and a 3D presentation to visually validate what was happening in the model. Each design scenario had hundreds of simulation replications covering variations in patient arrivals, different dose-limiting toxicity events (according to a probability curve), and several other factors.

The simulations showed a significant reduction in study durations for the IQ 3+3 and IQ Rolling 6 designs compared with their parent designs—right around 3.5 months for the standard scenario. We’ll get to what this means in a moment.

The IQ designs aren’t simply a theoretical experiment, either. The study lists six trials with completed phase 1 portions and another three ongoing phase 1 trials, all using the IQ designs. The earliest of these trials dates back to May 2012, so investigators, coordinating centers, and statistical teams are gaining valuable experience in queue-based designs.

Benefits for patients and pharmaceuticals

The quicker an effective cancer treatment can become available to patients, the better. So any safe and effective phase 1 oncology design that can reduce an average trial by 3.5 months is a big win for patients.

For pharmaceutical companies, clinical trial reductions are always beneficial, but for two very different reasons depending on the outcome of the drug.

Let’s say the drug will be shown to be a safe and effective treatment. Drug patents in the United States last for 20 years, but after FDA approval the actual time to sell a patented drug is typically between 7 and 12 years. Reducing phase 1 clinical trials by several months will add those months back to a company’s maximum patent royalties. In 2017, the median sales income across all cancer drugs was $435.2 million (or $1.2 million per day). So, adding 3.5 months of sales while under patent would add about $128 million in revenue for the average cancer drug.

But what if the drug doesn’t make it? No company wants their drug to be a bust, but it certainly helps to get that information a few months sooner and avoid the additional costs of an extended trial. So if you or someone you know is involved in designing phase 1 oncology trials, consider a new design update that could make a big impact.

Interested in using FlexSim Healthcare to validate and analyze a queue-based design for your upcoming trial? Contact us today and we’d be happy to discuss it with you.